Just a few years ago, low price herbal fuel was the primary force pushing coal out of the power generation marketplace, and now low price solar power is sneaking up on low price herbal gasoline. Thus far the competition is a trickle, now not a flood. However, natural gasoline stakeholders don’t have lots respiration room left, as indicated with the aid of the modern perovskite sun mobile studies.

Why A Perovskite Solar Cell?

The cost of solar power has already fallen off a cliff, primarily due to improvements in silicon solar cell technology and manufacturing, as well as improvements all up and down the silicon solar cell value chain. That’s why energy stakeholders in some US markets are already eyeballing solar power and hybrid wind-solar configurations as more economical alternatives to natural gas.

To push the transition faster, solar costs have to drop even farther, faster. That means finding a material that is more economical to work with than silicon, and that’s where the perovskite solar cell comes in.

For those of you new to the topic, perovskite solar cells are made with lab-grown crystalline materials based on the structure of the naturally occurring mineral perovskite. They are relatively inexpensive and easy to fabricate, and their unique optical properties make them ideal for solar applications.

Perovskites burst on the scene just a few years ago as a low cost replacement for silicon, and the research has been moving along at a rapid clip. Here in the US, the Department of Energy has been among the driving forces behind improving perovskite technology.

Now that some of the kinks have been worked out, researchers are focusing on boosting solar cell conversion efficiency while chopping away at manufacturing costs.

Yet Another Perovskite Solar Cell Breakthrough

One of the perovskite kinks still being worked out is the tradeoff between ease of production and solar cell efficiency. So far most of the research has focused on a polycrystalline structure because it is easy to produce in bulk quantities, though efficiency and stability are lost along the way.

Single-crystal perovskites are more efficient and stable, but until now nobody has figured out a pathway for getting the production process out of the small batch phase.

A team of nanotech engineers at the University of California – San Diego decided to take on the single-crystal challenge. The trick was to find a fabrication method that could translate into a high volume, high efficiency manufacturing model.

As the saying goes, they found it right there in their own backyard. The UC-San Diego research team deployed common fabrication processes that the semiconductor industry has used for many years to make single-crystal films from silicon and other materials that are ubiquitous in everything from cell phones to satellites.

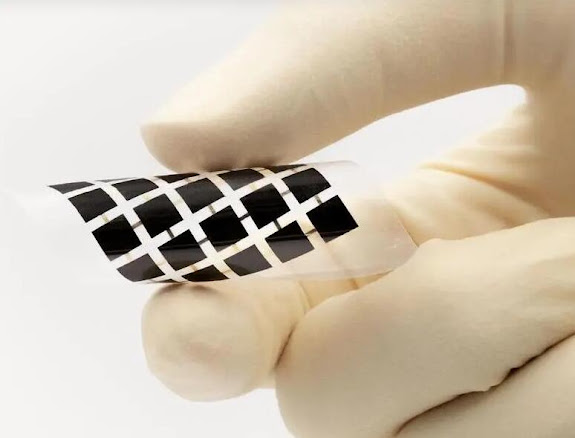

Single-crystal perovskite film produced with this equipment showed “fewer defects, greater efficiency, and enhanced stability [compared to] their polycrystalline counterparts,” enthused UC-San Diego in a press release last week.

How Did They Do That ?

Since there is no such thing as a free lunch, there has to be a catch somewhere. Or maybe not. Check out the team’s study in the journal Nature under the title, “A fabrication process for flexible single-crystal perovskite devices.”

Some of the heavy lifting was actually done two years ago, when the research team of UC-San Diego Professor Sheng Xu figured out a way to apply standard lithographic methods to perovskite film.

The combination of lithography and perovskites is quite a mountain to climb. One of the big kinks in the perovskite solar cell field is sensitivity to water, which is an essential element in lithography.

The solution involved shielding the perovskite film with a protective layer for the first part of the process, then using a dry etching step to finish it off.

The new research takes that process and refines it with a lithography mask pattern that enables precise control over the growth of the film.

“The method doesn’t require fancy equipment or techniques—the whole process is based on traditional semiconductor fabrication, further indicating its compatibility with existing industrial procedures,” explained the study’s first author Yusheng Lei, who is a nanoengineering grad student in Professor.

Natural Gas On The Run From The Solar Cell Of The Future

Although perovskite technology might not see widespread use within the next few years, all of this is bad new for natural gas stakeholders. They have enjoyed a head start on cost ever since 1956, when the first commercial solar cell hit the market at an eye-popping price of $300 per watt.

Now the average cost is down to just 50 cents per watt, the fully installed cost of a whole rooftop full of solar panels averages about $3.00 per watt, and some analysts are looking at widespread parity with natural gas in just a few years.

Natural gas stakeholders are also beginning to lose the baseload power argument, and they are rapidly losing their grip on the “clean” image.

Even if no perovskites appear on the horizon, the silicon solar cell of the future is set for another period of significant cost decline. Some analysts surmise that the COVID-related drop in demand for silicon solar panels has resulted in an oversupply that has already pushed prices down, and that impact will continue to spin out over the next several years even after the global economy recovers.

Another factor that should shiver the timbers of the natural gas industry is last month’s announcement from Meyer Burger, which brings a powerful new player into the global solar manufacturing picture right when the last thing anyone needs is more competition.

Here in the US, the Energy Department is also bent on driving down solar cell manufacturing costs.

Then there’s the whole field of solar soft costs, which includes labor, marketing, permits, grid connection and other costs that could be reduced through a national energy policy that incentivizes and subsidizes solar jobs and other elements of the solar industry.